Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS)

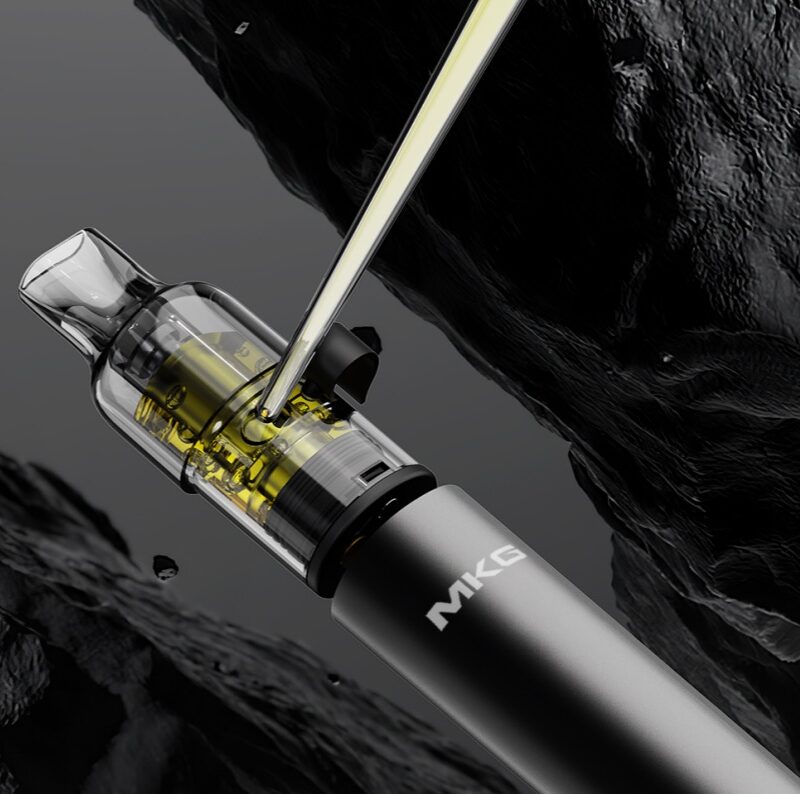

These products heat nicotine-containing liquids that may be synthetically or naturally derived from tobacco leaves. ENDS may contain fragrances and other ingredients to create aerosols (example: Twisp)

Electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS)

ENNDS heats non-nicotine liquids that may contain flavors and other ingredients to create aerosols (example: Eciggies Berry or Cinnamon Concentrates)

Heated tobacco products (HTP)

HTPs (also known as heat-not-burn products) consist of heat-treated tobacco leaves that allow users to inhale nicotine aerosols (examples: IQOS, Glo)

E-cigarette prevalence – in South African cities

4.0% were regular e-cigarette users (defined as at least once a week) at the time of the survey. More than half (58%) of these users also currently smoke. smoker.

1.5% used e-cigarettes regularly but later quit.

5.8% have tried e-cigarettes (defined as taking at least one puff, but never one puff per week in a typical month)

E-cigarette users – by type

dual user

Dual users are individuals who currently regularly use e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes.

The demographics of dual users are very similar to those of e-cigarette users. Dual use is less common among black people (1.4%) than other groups, more common among men (3.1%) than women (1.4%), and more common among younger people (3.2% among those under 34), Prevalence decreases with age.

E-cigarette users and combustible cigarette smokers

Twice as many of South Africa’s urban population have smoked or tried combustible cigarettes (26.8%) as those who report trying or using e-cigarettes (11.3%).

- Of those who had ever tried e-cigarettes, 35% were current users, compared with 47% who smoked combustible cigarettes.

- The most common form of e-cigarette use was experimental use (52%), and for combustible cigarettes, current use (47%).

- For e-cigarette users (13%) and combustible cigarette users (16%), regular past use was the least common form of use.

Among current users of combustible cigarettes and/or e-cigarettes, the majority smoked only combustible cigarettes (72%), compared with dual users (16%) and those who only smoked e-cigarettes (12%).

Order of use – electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes

- Among the 5.5% of urban South Africans who regularly use e-cigarettes (either currently or in the past): the majority (61%) started smoking combustible cigarettes before using e-cigarettes, while 39% had no previous use of combustible cigarettes history.

- Among people with no history of smoking: One in five (19%) started smoking after using e-cigarettes (on-ramper). Further exploration is recommended to understand why they started smoking.

- Among intruders: the majority (88%) were still smokers at the time of the survey. This equates to 5.6% of all e-cigarette users and 0.3% of South Africa’s urban population.

- Among the 17.1% of urban South Africans who regularly smoked combustible cigarettes (either currently or in the past): 17.3% started using e-cigarettes after starting to smoke combustible cigarettes.

- Of those who started using e-cigarettes after vaping combustibles: One in eight (13%) later quit (off-ramper). Further exploration is recommended to understand why they quit smoking.

- For many smokers, quitting is difficult and relapse is common. Most clinical trials characterize lifetime abstinence only among people who have been abstinent for at least 6 or 12 months. 11 12 In the TCDI sample, 44% of respondents classified as ex-smokers had quit smoking less than 1 year before the survey, including 27% who had quit smoking less than 6 months before the survey. Therefore, it should be noted that for about half (44%) of downhillers, lifelong abstinence is not certain.

*A note on prevalence statistics: The 2022 South African E-Cigarette Survey defines a regular smoker as someone who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smokes a cigarette at least once a day or week. The TCDI prevalence page reports smoking prevalence statistics for South Africa in the 2021 GATS.

The GATS definition of a current smoker differs from the TCDI definition in that it does not limit current smokers to:

1) Have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your life

2) Current smoker smokes at least once a week

Additionally, the GATS definition includes both hand-rolled and manufactured cigarettes, while the South Africa 2022 e-cigarette survey only includes manufactured cigarettes. The difference in prevalence of current smokers between these pages is due to these different definitions.

Excise tax – for e-cigarettes

Excise duty on e-cigarettes will be implemented at a rate of R2.90 per milliliter of e-liquid, regardless of nicotine content. This rate is one of the highest in the world.

This new e-cigarette tax is an important step for South Africa. In addition to an excise tax on e-liquid volumes, the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) has recommended that National Treasury should impose a minimum tax floor of R50 on all containers.

This recommendation was made because REEP showed that the tax proposal of R2.90 per milliliter would consistently generate a lower tax burden than the tobacco tax burden, while the tax of R5 per milliliter, which attempted to partially address this issue, was less effective. not enough. REEP suggests that a tax floor of R50 per unit of e-liquid would address this issue. In view of the pollution and environmental damage caused by disposable e-cigarette devices,

It is also recommended that they be taxed in the future.

Policy – for e-cigarettes

In light of growing evidence of the harm caused by e-cigarettes, more than 100 countries have passed laws regulating e-cigarettes, including African countries such as Egypt, Gambia, Mauritius, Senegal, Seychelles, Togo and Uganda. The most common forms of regulation are taxes, sales bans, usage restrictions (e-cigarette-free public places), purchase age requirements, and advertising and promotion bans.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that regulators in jurisdictions that do not ban e-cigarettes consider monitoring harmful compounds such as nicotine, aldehydes and carbon monoxide in e-cigarette emissions and, where appropriate, reducing their levels, in accordance with WHO recommendations and country-specific Condition.

South Africa lags behind other countries in e-cigarette legislation and has yet to enact a draft Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Bill, which proposes to treat e-cigarettes as traditional tobacco products, thereby regulating their use, marketing, sale and taxation of e-cigarettes.

To protect public health, comprehensive regulatory measures are needed to address e-cigarette advertising, marketing and sponsorship.

Demographic data on e-cigarette advertising in South Africa are needed to inform public health planning, practice and policy. However, available data is rather limited, with one study analyzing e-cigarette advertising exposure in 2017. This study shows:

- 20% of the sample reported being exposed to e-cigarette advertising. By age, exposure was most prevalent among those aged 16-19 years (24.6%).

- The top sources of exposure are stores (40.7%), shopping malls (30.9%) and television (32.5%).

- Among people who know about e-cigarettes, 61.2% believe that “e-cigarette advertisements and promotions may make teenagers have the idea of smoking traditional cigarettes”; 62.7% think that “e-cigarette advertisements and promotions may make quitters want to start over.” “The idea of smoking”; 59.5% of people supported the statement that “e-cigarettes should be banned indoors just like traditional cigarettes.”

Regarding the passage of the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Act, it was found that a report commissioned by the e-cigarette industry misrepresented the potential impact of restrictions on e-cigarette advertising and promotion, primarily by significantly underestimating the popularity of e-cigarettes. – Cigarette use in South Africa. Additionally, findings from a nationally representative study indicate that the number of e-cigarette users is far greater than indicated by industry-commissioned reports. By underestimating the prevalence of e-cigarette use in the population, these reports also underestimate the revenue-generating capacity of a potential e-cigarette excise tax proposed by South Africa’s National Treasury. Regulation of e-cigarettes will benefit public health in South Africa.

E-cigarettes: flavor ban

By 2022, more than 30 countries will not allow the sale of e-cigarettes as consumer products, and thus the sale of flavored e-cigarettes.

Among the countries that allow sales, six countries have implemented national bans on flavors other than tobacco flavors (Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands, Ukraine, Lithuania, China), and three countries have banned flavors other than tobacco and menthol (Denmark, Estonia and the Philippines, later withdrawn), and two other countries (Canada and the United States) enacted local restrictions.

Through administrative practice, the FDA has denied marketing orders for e-cigarettes with flavors other than tobacco and menthol. In South Africa, the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Act empowers the health minister to decide what and where South Africans smoke, which could spell the end for flavored e-liquids and e-juices.

African country regulations

Egypt: The Ministry of Health bans the sale of e-cigarettes. However, the Home Office is currently drafting new regulations to allow its sale and regulation. 20

Gambia: The Tobacco Control Act 2016 prohibits the sale, possession, distribution and import of nicotine-containing and non-nicotine e-cigarettes. All domestic and cross-border tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship are also banned.21.

Mauritius: The Public Health (Restriction of Tobacco Products) Regulations 2008 prohibit the sale or distribution of products that look like tobacco or cigarettes to anyone under the age of 18. The law also prohibits its advertising and promotion, and prohibits smoking in public places/vehicles outside designated areas. 22.

Senegal: Law No. 2014-14 (On the Manufacture, Packaging, Labeling, Sale and Use of Tobacco) was interpreted to include e-cigarettes. The law prohibits the advertising and promotion (direct or indirect) of tobacco, tobacco products and tobacco derivatives, as well as the advertising of non-tobacco products in a manner that may promote tobacco products. It also imposes restrictions on public smoking and packaging

Seychelles: The Tobacco Control Act 2009 prohibits the manufacture, import, supply, display, distribution or sale of imitation tobacco products.24.

Togo: The Tobacco Control Act of 2011 (and related decrees of 2013 and 2015) defines ENDS as tobacco “derivative products” and prohibits the provision of ENDS to anyone under 18 years of age, prohibits advertising and promotion, and prohibits Smoking in public places/transportation outside designated areas. ENDS face duties and fees, are not eligible for tax exemption, and are subject to a tax cap of 45%. Government officials believe these policies are also intended to regulate ENNDS, although this is not explicitly stated in the law. 25

Uganda: The sale, distribution, import, manufacture or processing of ENDS and ENNDS is prohibited under the Tobacco Control Act 2015. 26 The law does not address the use or advertising of e-cigarettes 27 .

Youth – e-cigarettes

Teenagers vulnerable to e-cigarettes

While detailed data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use among adolescents in South Africa is not available, data from the United States shows a rapid increase in the number of adolescents using e-cigarettes. One study found that in 2017, 25% of U.S. 12th graders had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. This has made e-cigarettes the most commonly used tobacco product among teenagers, rising rapidly from near-zero prevalence in 2011.

The high rate of e-cigarette use among young Americans has been attributed to lax marketing regulations. A study of U.S. teenagers who had never used e-cigarettes found a positive relationship between exposure to e-cigarette advertising and personal intentions to use e-cigarettes, and the relationship became stronger the more marketing channels teens were exposed to.

There is relatively little data on e-cigarette use among adolescents in developing countries, but recent surveys from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey sometimes include questions about e-cigarette use. These are typically nationally representative studies in which students (defined as school-based youth aged 13 to 15 years) are asked about their perceptions of e-cigarettes and their prevalence (defined as use within the past 30 days).

A 2017 study in Mauritius showed that e-cigarette use among students is relatively high: 54.2% of students are aware of e-cigarettes and 10.9% have used e-cigarettes (17.9% of boys and 4.3% of girls). In comparison, 13.6% of students in Mauritius smoke combustible cigarettes.

A 2016 study in Morocco showed that the prevalence of e-cigarettes among students was higher than that of cigarettes: 5.3% of students used e-cigarettes (6.3% of boys and 74.3% of girls), compared with 1.9% of smokers .

A 2016 Tunisian study showed that among Tunisian high school students aged 15 to 20, 58.8% had used e-cigarettes at least once, 38.3% had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days, and 20.5% had used them regularly e-cigarette.

A 2017 Georgia report showed that e-cigarette use among students was higher than the prevalence of cigarettes: 13.2% of students used e-cigarettes (compared to 17.3% of boys and 7.7% of girls), compared with 7.7% of students who smoked cigarettes. 8.4%.

A 2019 survey in Peru showed that e-cigarette use among students (6.3% of all students, 7.1% of boys and 5.4% of girls) was slightly higher than cigarette use (4.9%). 50

A survey conducted in China in 2013/2014 showed that students’ awareness of e-cigarettes was higher (45%), but the use rate of e-cigarettes was low (1.2%). Chinese young people say they use e-cigarettes for entertainment/habit rather than as an aid to quit smoking (among never smokers, e-cigarette users have a higher intention to use tobacco products in the next 12 months I than non-e-cigarette users) smokers).

36Between 2011 and 2020, the proportion of e-cigarette use among American high school students increased from 1.5% to 19.6%.

Teenagers believe e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes

Among Tunisian high school students:

- 53.8% of people think e-cigarettes are harmful, but 78.4% think e-cigarettes are less harmful than ordinary cigarettes.

- 50.5% believed they could be addictive. 45.4% of people believe that vaping can reduce anxiety, 33.3% believe that vaping makes them sociable, and 30.6% believe that vaping makes them confident.

E-cigarette users (vs. non-users) more generally believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful and less addictive than tobacco. E-cigarettes are more commonly thought to reduce anxiety and make users more sociable and confident.

Vape shops target South African youths

As the popularity of e-cigarettes increases in South Africa, the number of vape shops selling these devices and paraphernalia has also increased. As well as serving as points of sale, there are concerns that vape shops also serve as spaces that promote pro-tobacco perceptions of safety and social acceptability. These positive perceptions are important because they may lead to experimentation and ultimately continued use.

There is evidence that e-cigarette shops and companies specifically target young people, offering a range of flavors such as “cupcake” and “marshmallow,” leading young people to try and potentially continue to use e-cigarettes. In addition, e-cigarette stores and companies target young people by marketing e-cigarettes through discounts and other promotional programs, as well as opening e-cigarette stores close to college campuses. A study of 240 vape shops in South Africa found that 50% of these suppliers were located within a 5km radius of a higher education institution. The study also found that among adults ages 18 to 29, proximity to a vape store was associated with a higher likelihood of ever using e-cigarettes.

Slightly more dual users think e-cigarettes are more expensive than combustible cigarettes (39.4%) than those who think e-cigarettes are cheaper (38.1%), while 22.5% of dual users think e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes are equally expensive .